Will vs Fate: A Star Wars Essay

“There’s good in him,” said Padme, Luke, Ahsoka, and countless others. But what is good? What is the point of no return? There is an invisible gray line of mortality that many believe Anakin Skywalker crossed. The child of destiny, prophecy to bring balance, who falls into darkness, and is redeemed by the forgiveness of the Son. Few fictional characters are so established in the human consciousness as he is. And this becomes all the more interesting when you stop to consider that the moral of his story has conflicting interpretations depending on which version of this character you grew up with. So my question in this essay is what lesson are we meant to take from the life of Anakin Skywalker? As we'll see, that question goes a lot deeper than you may expect. Now, the first important point to acknowledge about Anakin Skywalker is that he is intergenerational, and this is true in two ways. His character arc takes place over generations in the Star Wars universe, and his story has also been told for generations in the real world.

Our culture first met Anakin as the diabolical space villain named Darth Vader in 1977, but his real character arc began with the release of The Phantom Menace in 1999. and key moments in his story have been revealed as recently as 2023. Because of this, his character is much more dynamic than most, and different people will perceive his character differently. So, right off the bat, that makes him a difficult character to analyze. The contours of his story are really a matter of perspective, an important thing to keep in mind. Now, the fact that Anakin is nine years old when he enters the story is, of course, significant, because it means his story begins in innocence. And try though you might, it's pretty hard to find any clues that Anakin carries the seeds of evil in this opening chapter. There is some literal foreshadowing in a brilliant promotional image, but we don't really get dark side vibes from young Anakin himself in the film. What we do get is speculation and suspicion from the Jedi and especially from Yoda, who senses that he may have a toxic attachment style. Now, the Jedi don't forbid love and compassion… per se, but they do have an issue with possessive attachment. Anakin's attachment to his mother is identified as an emotional liability. The morality of the Jedi will be important in our analysis, and there's a crucial dramatic irony in Anakin's relationship with them, as we'll see. Yoda maps out how Anakin might become tempted by the dark side in his famous dialogue about fear leading to anger, then to hate, then to suffering; but the most important thing we learn about Anakin in The Phantom Menace is that he is believed to be the chosen one, which raises the most important question in our analysis.

Does Anakin have a fixed destiny? Is his future predetermined even a little bit by an unseen cosmic force? Or is the outcome of his story determined exclusively by his decisions? And this might seem like a minor question, but really it's fundamental because any meaningful analysis of a character is fundamentally about the consequences of his or her moral decisions. And if Anakin was merely a puppet for the will of the force, then he never really made decisions of his own

The paradox of the self-fulfilling prophecy is very ancient in literature. Oedipus Rex is the classic example. This was written by Sophocles around two thousand five hundred years ago. It's the story about a man who tries to avoid his foretold destiny–that he'll kill his father and marry his mother–and it's his very attempt to prevent that outcome that ultimately causes it to occur. So here's why it matters for Anakin in trying to protect Padme: he ends up being the one who causes her death, so is that his fault, or was he bound to a future not of his own making? We'll come back to this question of prophecy and destiny in the conclusion of my analysis, but suffice to say, there are strong suggestions at the end of The Phantom Menace that Anakin's fate has already been at least inflected by the shadowy influence of the Sith.

Now, the next time we see Anakin, he's a young man, and almost immediately, we're given a dose of his insecurity and arrogance. Attack of the Clones is not especially subtle in establishing teenage Anakin as morally conflicted. He feels held back by Obi-Wan and the Jedi Council, and his blossoming romance with Padme makes him emotionally vulnerable. The film gives us a few key moments in Anakin's moral arc. One is that he increasingly defies his master, Obi-Wan Kenobi. Another is that he seems to jokingly suggest that the galaxy might best be organized as an autocracy. And ultimately, he violates the Jedi's prohibition against possessive attachment by secretly marrying Padme.

But of course, the most salient moral decision he makes in this film is the slaughter of Tuscan raiders. This is a reaction to his mother being kidnapped and murdered. And the thing that stands out about this outburst is that he admits openly to Padme that he killed the women and children, which, as we all know, puts him out of bounds of any morally acceptable act of retribution.

And he didn't just kill them, he, quote, “slaughtered them like animals.” I always thought this was an interesting choice from George Lucas because it strongly suggests that Anakin's character is irredeemable. And like any good tragic character, we, the audience, are challenged to confront the question of where to draw the line between that which is forgivable and that which is not.

Episode III, Revenge of the Sith, is certainly the darkest and most consequential chapter in Anakin's story. It's both ending and beginning, the pivotal metamorphosis, and Anakin's rebirth as Darth Vader. Immediately, it's clear that Anakin is already gripped by the dark side; however, that doesn't mean he's not still morally conflicted at this point.

The beheading of Count Dooku is one of the most important moments in Anakin's arc. It binds Anakin to evil in a way that's unprecedented in the story. He's now complicit in the crimes of the nascent Imperial regime. It's not quite Anakin's point of no return, because you could still justify Dooku's execution as a necessity of war in the service of a greater good for the galaxy. But given how early it is in the story, things aren't looking so good for little Ani. And of course, the scene is meant to prefigure the throne room scene and give further moral context to Anakin's ultimate redemption, which we'll get to.

Another important moment for Anakin is when he is denied the rank of master. Now, he's not just getting passed over for a promotion here. It's a deep betrayal and a critical rift between the two moral systems that compete for Anakin's soul. In asking him to spy on Palpatine, they expose their own deceit and corruption, playing right into Palpatine's hands. One must remember that the main reason Anakin is drawn to Palpatine is that he's pushed away by the Jedi. And this is hugely important for the analysis because in many ways, Anakin's fall is a consequence of the moral shortcomings of the Jedi. their rigid code prohibiting emotional attachment, their lack of regard for their “expendable” clone armies, and their suspicion of Anakin. It all leads to their downfall. Again, it's the self-fulfilling prophecy: their fear that Anakin is a threat is ultimately what makes him one.

Palpatine is often framed as a puppet master in this classic tale, but he is actually passive if you look closely. Yes, he is manipulating things, but he also stands back and allows the Jedi to be their own undoing, waiting in the wings until the right moment to tempt Anakin with a compelling alternative to the one that he is increasingly disillusioned by. That is accelerated by Anakin's visions of Padme's death, which Palpatine promises can be prevented, assuming certain moral compromises are made (namely converting to the dark side).

At last, Anakin does finally figure out that Palpatine is a Sith and, at first, does the right thing by warning his boss, Mace Windu. And it's only after Palpatine gives Anakin the final ultimatum of switching to the dark side or losing Padme, that Anakin at last makes his final, fateful choice by killing Mace Windu, the second highest ranking Jedi Master after Yoda. “You're fulfilling your destiny, Anakin,” Palpatine sneers.

There's a moment in Shakespeare's McBeth where, after a series of increasingly immoral acts, McBeth murders King Duncan, which is often interpreted as the moment when the character McBeth crosses the line into irredeemable evil–it's all downhill after that. So, I want to pose a question: is this Anakin's King Duncan moment? Is this the point of no return for Anakin?

In this moment, it truly seems that he fully embraces the dark side. He now appears totally obedient to Palpatine and dutifully executes Order 66 with almost no apparent conflict or remorse, including what might be the most intimately evil moment in his character arc, the slaying of the younglings. Things go from bad to worse when he force chokes the person he's purportedly trying to protect. And well, suffice to say, in his relationship with Obi-Wan, he does not appear to end up on the moral high ground.

There has been much criticism of the apparent abruptness of Anakin's transformation from the heroic “General Skywalker” into the black capewearing Darth Vader. So, I found it really interesting that the TV series Kenobi attempted to at long last to give us the on-screen synthesis of the two distinct images of Anakin. This was done by showing actor Hayden Christensen inside the Vader mask and by blending his natural voice with Vader's voice to really great effect. “Anakin's gone… I am what remains.” It's hard not to get emotional watching this scene. Obi-Wan apologizes for failing Anakin, to which he replies, "You didn't kill Anakin Skywalker, I did." This is enormous because it reframes Anakin's fall as an act of free will, something he decided rather than something that was done to him, which has huge moral implications. But more importantly, it seems to separate Anakin and Vader into two distinct characters; if this is how we interpret his arc, then we could see Anakin as a victim of Darth Vader. But there's another really interesting interpretation of this scene, and that is that Anakin is actually forgiving Obi-Wan. Anakin knows that Obi-Wan feels guilty, so his saying that the choice was his in a roundabout way absolves Obi-Wan of his guilt. This brings us to a crucial transition in how we understand Anakin's character. Where the prequels show us his fall from grace, the original trilogy—created decades earlier yet set decades later—approaches him from an entirely different angle. Here, we must grapple with Vader not as the conflicted young man we've come to know, but as the established enforcer of galactic tyranny.

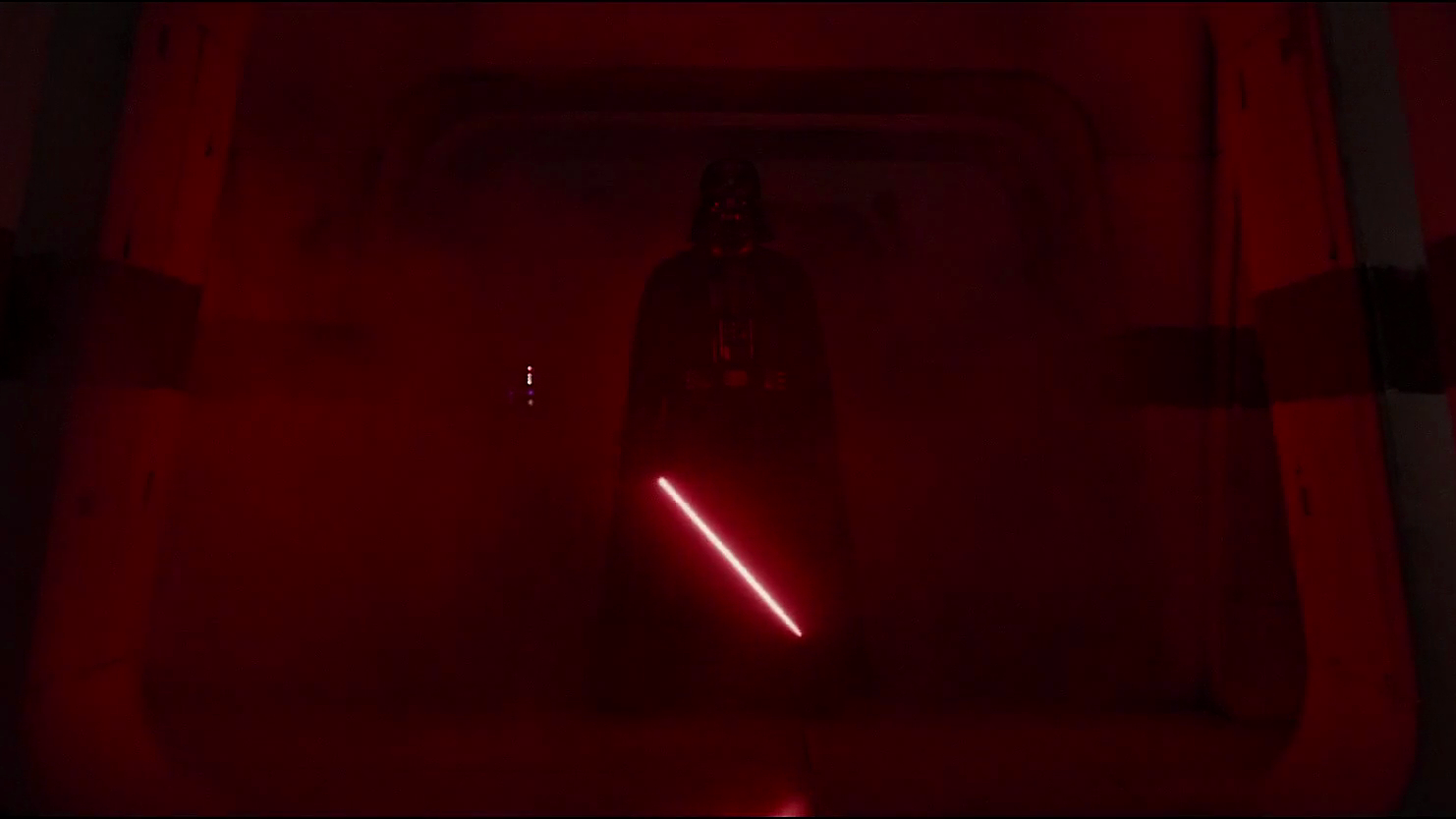

But before you get all misty thinking about what a victim Anakin is, remember that his next major appearance is in Rogue One, in which he indiscriminately massacres rebel soldiers with no apparent regard for human life. There is not a trace of sympathy in this depiction of him, and it might even be the most classically evil we've ever seen him. I suppose that's appropriate because the original trilogy that this film sets up also does not give us many clues about the man inside the machine.

However, really, there isn't a lot we can say about Anakin's character development in episodes 4, 5, and 6 because the story is, of course, much more about his son. A New Hope frames Vader as a henchman of the Galactic Empire. Episode 5 has a little more to say about Anakin. It introduces Palpatine, the all-powerful Galactic Emperor. But of course, the most important moment here is Anakin revealing his true identity to his son, which puts his obsession with uncovering the Rebellion into its proper context. We don't see many facial expressions from Darth Vader, from which to infer his more subtle motivations, but watching this film in full view of the saga, it's clear that Anakin has a desire to have a relationship with Luke, even if the stated purpose of capturing him is to turn him to the dark side. The Empire Strikes Back is one of the most interesting chapters in Anakin's story for this reason. As a viewer, are you meant to perceive the good in Anakin at this point in the story? It's an interesting question. I mean, he doesn't seem to mind cutting Luke's hand off. Then again, maybe it's because he wants Luke to be like him, to follow in his footsteps, as it were.

There is another crucially important scene in this film, and that is Luke's vision in which his own face is revealed to be inside Vader's mask. Again, in full view of the saga, this is much more than foreshadowing Luke's lineage. It can also be interpreted as being part of Anakin's arc, because it's the moment that the mistakes of the father are rendered as a warning to the son. Now, the saga does have many discontinuities, but I think this scene actually takes on a deeper meaning in light of the prequels. This is Luke's “fear leads to suffering” moment. Not the suffering of others: his own suffering. And in both cases, this is a lesson from Yoda. So by episode 6, all the pieces are in play for what I believe is one of the most profound redemption tales ever told.

The first thing that Anakin does in this chapter is kneel before Emperor Palpatine, which is very important because it reminds the viewer that Anakin is subservient to a greater villain, one who is purely and indisputably evil with no redeeming qualities. So, right from the beginning of Return of the Jedi, Anakin is already much more sympathetic, and the space is created for his character to develop in an unexpected direction. Now, again, if you're able to remember baby Anakin behind the mask, you really feel the fact that Anakin is a prisoner of Palpatine. By the middle of the film, there are strong hints that Anakin has a shred of humanity left in him. But of course, the throne room scene is where all of the saga's complex moral algebra reduces to its final formula.

Despite being one of the most sprawling stories ever told, Anakin's moral arc resolves in a very simple conclusion. And one of the most beautiful aspects of this story is that Luke and Anakin, father and son, save each other. First, when Luke cuts off Anakin's hand, the same hand that he lost way back in Attack of the Clones, he realizes that he is embodying the very evil that consumed his father. He chooses self-sacrifice, refusing to submit to fear and anger. Then, Anakin, seeing this act of selflessness, realizes that his alignment with Palpatine has cost him everything, and at last, chooses to sacrifice himself. It rhymes, sort of like poetry. It's a beautiful scene, but there is, of course, one last and necessary step in Anakin's moral journey, and that is his unmasking. For all of the Gungans and cheesy romance you'll find in Star Wars, all of its follies and missteps, I don't think it's hyperbole to say that Luke's unmasking of Anakin is one of the most profound dramatic scenes ever created, and I mean that even in the full scope of literary history.

There is incredible moral depth in this scene. Importantly, Anakin asks Luke to remove the mask even though it will kill him. And the fact that it's Anakin's choice is so crucial because it's his will at play in this scene more than Luke's; it's a clue that this is the resolution of Anakin's character, not of Luke's. The man behind the mask appears weak and frail, far from the villain we have assumed him to be. The precise moment of Anakin's moral resolution can be pinned down to just three words of George Lucas dialogue. Luke says, "I've got to save you." And Anakin replies, "You already have." That line is monumental in its moral implications. In believing, despite all evidence to the contrary, that there was some good in Vader, Luke has given Anakin one final shot at redemption.

Now, like any good character, there are many interpretations of Anakin's moral arc. The most obvious moral problem with Anakin is that he is, to some degree, responsible for the suffering of millions. It's not necessarily a foregone conclusion that Anakin deserves forgiveness or redemption. Is the lesson meant to be that even the most evil people ought to be forgiven in the end? Well, that really depends on how much of Anakin's story was predetermined by destiny. Remember, little Anakin was believed to be the chosen one who would bring balance to the force and destroy the Sith. And I think the most common interpretation is that Anakin's fall and eventual redemption is ironically the fulfillment of that prophecy. He does after all ultimately destroy the Sith just as Qui-Gon Jinn had hoped. If that's how we understand the prophecy, then we are, by implication, granting that Anakin's terrible deeds were at least, to some degree, pre-ordained by a higher power and therefore not committed of Anakin's individual will and therefore not entirely Anakin's fault. The youngling incident, according to this “certain point of view”, is just another step on the journey laid before him by his destiny.

Anakin's character is morally ambiguous. The question of whether he is either of the two conditions we call good and evil is oversimplistic and reductive. The reason we are fascinated by Anakin Skywalker is precisely because we cannot truly know him. Depending on who you are, which parts of Star Wars you've watched, read, or played, you will interpret Anakin in your own unique way. Maybe you think he's a tragic figure, a victim of circumstances beyond his control. Maybe you think he's a formidable villain, scourge of the galaxy. Maybe you think he's a conflicted hero who struggles to do good in a world increasingly consumed by darkness. Is his story a warning against dogmatism and corruption, against the temptations of power, or against the suffocating prison of self-denial? The fact that he is both hero and villain, victim and oppressor, dark and light, is exactly the point.

Generations have watched his story unfold, and generations more will debate his choices. But that is precisely what makes Anakin Skywalker immortal: not his power, not his fall, not even his redemption, but his refusal to be anything less than impossibly, devastatingly human.